|

Gypsy

Smith (1860-1947)

His

Life and Work

By Himself

|

| Chapter

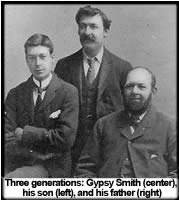

25. My Father And His Two Brothers |

|

Let me interrupt my personal narrative

for a little to tell my readers some things about my father and his two remarkable

brothers that will, I think, interest them.

My father, Cornelius Smith, though in his seventieth year, is still hale and

hearty. He lives at Cambridge, and, even in the fullness of his years, spends

most of his time in religious work. There are few evangelists better known in

the Eastern Counties. When he goes to a place that he has not visited before,

he always begins his first discourse by saying: "I want you people to know

that I am not my son, I am his father."

I wrote my father's first love-letter. This is how it came about. My readers

will remember that my mother died when I was very young. My father married again,

some time after his conversion, but his wife died in less than a year. When,

twenty two years ago, the last of his daughters (now Mrs. Ball) was about to

get married and to leave him all alone in his tent, my father came to me in

very disconsolate mood, saying –

"What shall I do now?"

"Will you live with me if I get married? " I said. " No, I'd

rather not; I've always had a little corner of my own."

"Well, why don't you get married yourself?" My father was forty-seven

at this time, and he looked younger.

"Oh, come now, whom could I marry?"

"Well, I think I know a lady who would have you."

"Who? "

"Mrs. Sayer."

My father looked both surprised and delighted.

"How do you know that?" he asked.

"Well, when I was working at the Christian Mission, Whitechapel, and you

used to come to see me, Mrs. Sayer often came too, and she was for ever hanging

about me, for you were always in my neighbourhood. One day I said to her, "Do

you want any skewers or clothes-pegs today, lady? " She was taken aback,

seemed to guess what I meant, and smacked me in the face.

"Well," said my father, "it is strange that I have been thinking

about Mrs. Sayer too. It is some years since first I met her, and I've seen

her only very occasionally since, but she has never been out of my mind."

"Shall I write to her, then, for you?"

"Yes, I think you had better."

My father outlined what he desired me to say in proposing to Mrs. Sayer, and

after I had finished the letter I read it to him. He interrupted me several

times, remarking, "Well, I did not tell you to say that, did I?" and

I replied, "But that is what you meant, is it not?" Soon after Mrs.

Sayer, who at that time was a Captain in the Salvation Army, and had been previously

employed by Lord Shaftesbury as a Bible-woman in the East-end, and my father

were married. It has been one of the chief joys of my life that I had something

to do with arranging this marriage, for it has been a most happy union. In the

year of this marriage my father's brother Woodlock died, and two years later

the other brother, Bartholomew, died. "The Lord knew," my father has

said, "when He took away my dear brothers that I should feel their loss

and feel unfit to go to meetings alone; so my wife was given to me. And the

Lord is making us a great blessing. Our time is fully spent in His work, and

wherever we go souls are saved and saints are blessed."

When my father was converted he did not know A from B. But by dint of much hard

battling, at a time of life too when it is difficult to learn anything, he managed

to read the New Testament, and I doubt whether anybody knows that portion of

Scripture better than my father does. I do not know any preacher who can in

a brief address weave in so many quotations from the New Testament, and weave

them in so skilfully, so intelligently, and in so deeply interesting a manner.

My father has an alert mind, and some of the illustrations in his addresses

are quaint. During my mission at the Metropolitan Tabernacle he spoke to the

people briefly. His theme was "Christ in us and we in Christ," and

he said, "Some people may think that that is impossible; but it is not.

The other day I was walking by the seaside at Cromer, and I picked up a bottle

with a cork in it. I filled the bottle with the salt water, and, driving in

the cork, I threw the bottle out into the sea as far as my right arm could send

it. Turning to my wife, I said, "Look, the sea is in the bottle and the

bottle is in the sea." So if we are Christ, we are in Him and He is in

us."

Before my conversion, while I was under deep conviction of sin, I used to pray,

"O God, make me a good boy; I want to be a good boy; make me feel I am

saved." In my young foolishness of heart I was keen on feeling. My father

had heard me pray, and had tried to meet my difficulty, but without success.

However, it chanced that one afternoon we were invited to drink tea at the house

of a friend in a village where the three brothers were holding a mission. Attached

to the house was a beautiful large garden, containing many heavily-laden cherry-trees.

My father was as merry and whole-hearted as a boy, and not ashamed of liking

cherries, and we all went out to pick the fruit. Presently I was amazed to observe

my father gazing up steadfastly at the cherries and saying, in a loud, urgent

voice, as he kept the inside pocket of his coat wide open, "Cherries, come

down and fill my pocket! Come down, I say. I want you." I watched his antics

for a moment or two, not knowing what to make of this aberration. At length

I said –

"Daddy, it's no use telling the cherries to come down and fill your pocket.

You must pluck them off the tree.''

"My son," said my father in pleased and earnest tones, "that

is what I want you to understand. You are making the mistake that I was making

just now. God has offered you a great gift. You know what it is, and you know

that you want it. But you will not reach forth your hand to take it."

My father was frequently engaged by a gentleman in Norwich, Mr. George Chamberlain,

to do evangelistic work in the vicinity. At the time of this story there was

an exhibition of machinery in connection with the Agricultural Show then being

held in the old city. Mr. Chamberlain gave my father a ticket of admission to

it, saying, "Go, Cornelius, see what there is to be seen; it will interest

you. I'm coming down myself very soon." When Mr. Chamberlain reached the

ground he found my father standing on a machine, with a great crowd, to whom

he was preaching the Gospel, gathered round him. He gazed upon the spectacle

with delight and astonishment. When my father came down from this pulpit, Mr.

Chamberlain said to him -

"Well, Cornelius, what led you to address the people without any previous

arrangement, too, and without consulting the officials? I sent you here to examine

the exhibits."

"That's all right," said my father; "but the fact is I looked

round at all the latest inventions, and I did not see one that even claimed

to take away the guilt and the power of sin from men's hearts. I knew of something

that could do this, and I thought these people should be told about it. There

were such a lot of them, too, that I thought it was a very good opportunity."

My father was on one occasion preaching in the open air to a great crowd at

Leytonstone. A coster passing by in his donkey-cart shouted out: "Go it,

old party; you'll get 'arf a crown for that job!" Father stopped his address

for a moment, looked at the coster, and said quietly, "No, young man, you

are wrong. My Master never gives half-crowns away, He gives whole ones. 'Be

thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life.'" The coster

and his "moke" passed on.

I have said before that the three gipsy brothers, after their conversion, always

travelled the country together. Wherever they went they never lost an opportunity

of preaching. And their preaching was very effective, for the people, knowing

them well, contrasted their former manner of life - lying, drinking, pilfering,

swearing - with the sweet and clean life they now led, and saw that the three

big, godless gipsy men had been with Jesus. They beheld a new creation. When

they came to a village the three big men - my father was six feet, broad in

proportion, and he was the smallest of them - accompanied by their children,

took their stand in the most public place they could find and began their service.

The country folk for miles around used to come in to attend the meetings of

the three converted gipsy brothers. Each of them had his special gift and special

line of thought. Uncle Woodlock, who always spoke first, had taught himself

to read, and of the three was the deepest theologian - if I may use so pretentious

a word of a poor gipsy man. He was very strong and clear on the utter ruin of

the heart by the fall, and on redemption by the blood of Christ, our substitute.

Over the door of his cottage at Leytonstone he had printed the words, "When

I see the blood I will pass over. It was very characteristic.

After Woodlock had made an end of speaking, the three brothers sang a hymn,

my father accompanying on his famous "hallelujah fiddle." Uncle Bartholomew,

never to the day of his death could read, but his wife could spell out the words

of the New Testament, and in this way he learned by heart text after text for

his Gospel addresses. His method was to repeat these texts, say a few words

about each, and conclude with an anecdote. My father came last. It was his part

to gather up and focus all that had been said, and to make the application.

He had a wonderful power in the management of these simple audiences, and often

melted them into tears by the artless pathos of his discourses. But the most

powerful qualification these evangelists had for their work was the undoubted

and tremendous change that had been wrought in their lives. Their sincerity

and sweetness were so transparent. It was clear as daylight that God had laid

His hand upon these men, and had renewed their hearts.

Until the marriage of which I have told in this chapter, my father lived in

his waggon and tent, and still went up and down the country, though not so much

as he had done in his younger days. I told him that he could not ask Mrs. Sayer

to come and live with him in a waggon. She had never been used to that. He must

go into a house. I suggested that he should buy a bit of land, and build a cottage

on it. "What!" he said, "put my hard-earned money into dirt!"

However, he came round to my view. The three brothers each bought a strip of

territory at Leytonstone and erected three wooden cottages. But they stood the

cottages on wheels.

Uncle Woodlock was not so fortunate in his wife as the other two brothers. She

was not a Christian woman, and she had no respect and no sympathy for religious

work. When Woodlock came home from his meetings his wife would give him her

opinion, at great length and with great volubility, concerning him and his preaching.

The poor man would listen with bowed head and in perfect silence, and when she

had finished her harangue, he would say, "Now, my dear, we will have a

verse," and he would begin to sing, "Must Jesus bear the cross alone?"

or, "I'm not ashamed to own my Lord or, "My Jesus, I love Thee."

Uncle Barthy's wife was a good, Christian woman, and is still on this side of

Jordan, adorning the doctrine of the Gospel. When I was conducting the simultaneous

mission campaign at the Metropolitan Tabernacle she came to hear me. The building

was crowded, and the policeman would not let her pass the door. "Oh, but

I must get in," she said; "it's my nephew who is preaching here. I

nursed him, and I'm going to hear him." And she was not baffled.

The brothers were not well up in etiquette, though in essentials they always

behaved like the perfect gentlemen they were. They were drinking tea one afternoon

at a well-to-do house. A lady asked Uncle Woodlock to pass her a tart. "Certainly,

madam," said he, and lifting a tart with his fingers off the plate handed

it to her. She accepted it with a gracious smile. When his mistake was afterwards

pointed out to him, and he was told what he ought to have done, he took no offence,

but he could not understand it at all. He kept on answering: "Why, she

did not ask me for the plateful; she asked for only one!"

Woodlock and Bartholomew have now gone to be for ever with the Lord who redeemed

them, and whom they loved with all the strength of their warm, simple, noble

hearts.

Uncle Woodlock was the first to go home. The three brothers were together conducting

a mission at Chingford in March, 1882. At the close, Woodlock was detained for

a few minutes in earnest conversation with an anxious soul. My father and Bartholomew

went on to take the train for Stratford, leaving Woodlock to make haste after

them. Woodlock, in the darkness, ran with great force against a wooden post

in the pathway. It was some time before he was discovered lying on the ground,

groaning in agony. To those who came to his help he said, "I have got my

death-blow; my work on earth is done, but all is bright above; and I am going

home." His injuries were very severe, and though his suffering was great,

he never once lost consciousness. My father stayed by him all night, while Uncle

Barthy returned to Stratford to tell the families about the accident. When morning

dawned, Woodlock's wife came to see him, and then he was removed to his own

little home in Leytonstone, where he breathed his last. Within an hour of his

departure he turned to his weeping relatives, and said, "I am going to

heaven through the blood of the Lamb. Do you love and serve Jesus? Tell the

people wherever you go about Him. Be faithful: speak to them about the blood

that cleanses." Then, gathering himself up, he said, "What is this

that steals upon my frame? Is it death?" and quickly added –

"If this be death,

I soon shall be

From every sin and sorrow free.

I shall the King of Glory see.

All is well!

He had been ill for twenty-eight hours.

He lies buried in Leytonstone churchyard, awaiting the resurrection morn. He was

followed to his grave by his sorrowing relatives and over fifty gipsies, while

four hundred friends lined the approach to the church and burying-place. The parish

church had a very unusual congregation that day, for the gipsy people pressed

in with the others, and as the Vicar read the burial service, hearts were deeply

touched and tears freely flowed. At the grave, the two surviving brothers spoke

of the loved one they had lost, and told the people of the grace of God which

had redeemed them and their brother, and made them fit for the inheritance of

the saints in light. Woodlock was a hale man, only forty-eight years of age.

Two years later Uncle Barthy followed his brother Woodlock into the kingdom of

glory. He died in his own little home at Leytonstone, but most of the days of

his illness were spent in Mildmay Cottage Hospital. All that human skill could

devise was done for him, but he gradually grew weaker, and asked to be taken to

his own home. A few hours before he passed into the presence of God he called

his wife and children around him, and besought each of them to meet him in heaven.

In his last moments he was heard to say, "There! I was almost gone then -

they had come for me!" When asked who had come, he replied, "My Saviour."

to his wife, he said, "You are clinging to me; you will not let me go; and

I am sure you do not want me to stay here in all this pain. I must go home; I

cannot stay here. God will look after you. He knows your trouble, and He will

carry you through." The poor woman was expecting a baby in a few months.

My father tried to comfort her, and to teach her resignation to the will of God.

"Tell the Lord," he said, "that you desire His will to be clone."

She said, " Oh, it is so hard!

"Yes," answered my father, "but the Lord is going to take Bartholomew

to Himself. It will be better for you if you can bring yourself to submit with

resignation to His will."

Those gathered round the bedside then knelt down. The dying saint sat up in bed

with his hands clasped, looking at his wife, whilst she poured out her soul before

the Lord and told Him her trouble. God gave her the victory. She rose from her

knees exclaiming, "I can now say, "Thy will be done!" She gave

her husband a farewell kiss. Immediately he clapped his hands for joy and said,

"Now I can go, can't I? I am ready to be offered up. The time of my departure

is at hand. Lord, let Thy servant depart in peace. Receive my spirit, for Jesus'

sake!" And so Bartholomew's soul passed into the heavenly places. The whole

bedchamber was filled with glory. Uncle Barthy rests in Leytonstone churchyard

beside his brother Woodlock. In death they are not divided.

It is strange rather that my father, the oldest of the three brothers, should

live the longest. It is seventeen years since the death of Uncle Barthy. My father

is like a tree planted by the rivers of water, still bringing forth fruit. When

I go to see him I kneel at his feet, as I used to do when I was a boy, and say,

"Daddy, give me your blessing. All that I am I owe, under God, to the beautiful

life you lived in the old gipsy waggon." And with a radiant heavenly smile

on that noble old face, he answers, with tears of joy in his eyes, "God bless

you, my son! I have never had but one wish for you, and that is that you should

be good." Some time ago, when I was conducting a mission at Torquay, I talked

to the people so much about my father that they invited him to conduct a mission

among them. And then they wrote to me: "We love the son, but we think we

love the father more." They had found that all that I had said about my father

was true.

Back to Table

of Contents